"Their Dreams, Their Rights, and Their Love" A LGBTQ+ History Audio Tour

Join us on a ten-stop tour exploring Boston’s historic LGBTQ+ community and consider the ways they asked and answered the fundamental American questions - about freedom, voice, and how change is made - in their own time and ways.

Massachusetts State House

Capital of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts

Capital of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts

Transcript

Welcome to the National Park of Boston’s “Their Dreams, Their Rights, and Their Love:” A LQBTQ+ Tour of Beacon Hill and Downtown Boston. This tour will look at some of Boston’s unique lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer, or LGBTQ+ history. Boston is widely known as the “Cradle of Liberty” for its role as a place for social and political activism in the early days of the American Revolution. On our tour today, we will examine some of the central questions that stem from that Revolution and continue to shape our lives today ... What does freedom look like and who is it for? And... how are voices heard...and how is change made... in our nation? The founders grappled with these questions, as has every subsequent group and generation including Boston’s historic LBGTQ+ community. Freedom for this community meant the freedom to live and love publicly and authentically, without fear of harassment, imprisonment, or harm...as well as the freedom to create and sustain community and to advocate for their rights in a country that promised “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” to all. They made their voices heard in letters, print, creative expression, and fierce political activism. Fittingly we begin today at the Massachusetts State House, a crucial site of heated debate and protests, setbacks, long sought for victories, and joyous celebration. Beginning in the early 1970s, inspired by the Civil Rights Movement, and championed by some of its key local leaders including Representatives Mel King and later Byron Rushing, gay rights activists and their allies took their fight to the State House. State lawmakers including Barney Frank put forth legislation that prohibited discrimination based on sexual orientation in employment, housing, credit, and public accommodations. Shot down several times in the 70s and 80s, this law finally passed in 1989, a major milestone for Gay and Lesbian civil rights. It took 17 years and multiple debates and votes to finally protect people from losing their jobs, housing, and access simply for being who they were. While this legislation helped to secure individual rights, the next major struggle focused on relationship rights including the right to foster children, as well as the right to marry. In the fight for Marriage Equality, the State House, both inside and out, once again became a battleground. Inside, political leaders debated both for and against same-sex marriage. Outside, supporters and opponents rallied and protested in huge numbers. Finally, in 2003, in the Goodridge v. Department of Public Health case, the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts ruled that banning same-sex marriage was unconstitutional. While many gathered at the State House to protest this ruling, thousands turned out here to celebrate this milestone victory. With this ruling, in 2004, Massachusetts became the first state in the country to legalize same-sex marriage. Now, before we dive any further into this tour we must discuss some terminology, sources, and barriers to learning about Boston’s historic LGBTQ+ history. For most of our tour, unless someone has clearly labeled themselves, we will identify people as queer. The meaning and connotation of Queer has changed a lot over time. Once considered derogatory, many folks within the LGBTQ+ community have since reclaimed the word. We will be using the word “queer” as an umbrella term to recognize someone who fell outside of the norms of their time on the wide spectrum of sexuality. The word allows us to recognize the many forms of relationships and gender expressions without assuming we can know all the details of a person’s experiences. We also have to consider some of the historical barriers to learning this history. People did not begin labeling their sexual and gender orientation openly until the mid -1900s. Before that, people vaguely alluded to or outright omitted their same-sex relationships in their writings. Other times, historians, archivists, or even family members attempted to conceal any references to these types of relationships. Despite these barriers to research, we hope our tour today will give you a look into some of the city’s LGBTQ+ history as it relates to the Beacon Hill neighborhood as well as some prominent sites downtown. Along the way we will stop at homes, churches, gathering spaces, and sites of struggle and celebration. We will look at the private lives of specific individuals, as well as the collective public efforts of folks. Please keep in mind that many of the sites along our tour are private residences and not open to the public. And with that, let’s head down Beacon Street to our next stop. As we walk, look across the street at Boston Common. The Common has served as a central staging ground for Boston’s Pride Celebration since the early 1970s

In the struggle for LGBTQ+ rights, the Massachusetts State House served as a crucial site of heated debate, protests, setbacks, long sought for victories, and joyous celebration. In the early 1970s, gay rights activists and their allies took their fight to the State House. Lawmakers put forth legislation that prohibited discrimination based on sexual orientation in employment, housing, credit, and public accommodations. After 17 years, the law finally passed in 1989. In the subsequent fight for Marriage Equality, the State House, both inside and out, once again became a battleground. Inside, political leaders debated both for and against same-sex marriage. Outside, supporters and opponents rallied and protested in huge numbers. In 2003, the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts ruled that banning same-sex marriage was unconstitutional. While many gathered at the State House to protest this ruling, thousands turned out here to celebrate this milestone victory.

Directions to next stop

Walk down Beacon Street, with Boston Common on your left. Turn right onto Walnut Street. Please note, as you walk through Beacon Hill, there are many uneven sidewalks. Please watch your step. Turn left onto Chestnut Street. Walk on the right side of the street. The Howe house is at 13 Chestnut Street.

Samuel Gridley and Julia Ward Howe House

13 Chestnut Street, home of Sameul Gridley and Julia Ward Howe

13 Chestnut Street, home of Sameul Gridley and Julia Ward Howe

Transcript

We are now at the home of Samuel Gridley and Julia Ward Howe, prominent social reformers in mid-1800s Boston. This south side of Beacon Hill was the home of Boston’s “Brahmins,” the wealthy white upper class community. Within this Brahmin neighborhood was a small, not often discussed, queer community. In the 1800s, queer relationships looked and were defined very differently than they are today. For example, the ambiguous intimate relationships between people of the same sex back then are often described as “Romantic Friendships.” Sometimes, these relationships blurred the lines between romantic and platonic love and were often the most important ones in people’s lives. Several notable Beacon Hill figures fall into this category, including the famous abolitionist lawyer and Senator, Charles Sumner. While we may never know how he identified, we know that he viewed his relationships with both Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Samuel Gridley Howe as the two most significant relationships in his life. Devastated when Longfellow married Fanny Appleton, Sumner thought his relationship with him would be over. Luckily, Fanny welcomed him into their home and even invited Sumner to accompany them on their honeymoon. Sumner dined with the Longfellows at least once a week. The letters exchanged between Charles and Henry show an extraordinary and genuine love for each other. Sumner appears to have had a similar relationship with Samuel Gridley Howe. When Samuel married Julia Ward...Sumner thought it would mark the end of their relationship as well. And this time he was correct. Samuel struggled with his relationship with Sumner, often pushing Sumner away but then needing him. His relationship with Sumner clearly impacted his wife. Julia complained her husband did not love her and instead preferred the company of others, often singling out Sumner. In a letter to Sumner, Samuel wrote: When my heart is full of joy or sorrow it turns to you & years for your sympathy; in fact as Julia often says –Sumner ought to have been a women & you to have married her. But I should not agree to this in any monygamic land, for Julia is my love as a wife.” Eventually, the strain of Samuel’s feelings and marriage lead to his relationship with Sumner falling apart. While we are able to see the intensity of Sumner’s relationship with Howe in their writings that we have, we can never truly know how either of them identified. Not only did they not use the language we use today, but they also often burned or cut up letters sent between them, destroying writings that could have helped us gain more insight. For example, Samuel wrote to Sumner: "I have made a rule lately to put in the only place such notes of yours as might be disagreeable to you to have seen by unfriendly eyes – on the grate. It costs me something to burn a piece of paper that has been hallowed to my eye by the impression of your hand, but I do it. I have no confidant for such things – no! Not one!” This intentional obscuring if not outright destruction of evidence of these relationships is one reason that it is harder to identify queer people of the past. While the story of Howe and Sumner gives us a window into the private lives of two very public men, our next stop will look at the ways that a more recent LGBTQ+ community was able to publicly claim space and advocate for their rights to live openly and authentically.

At the home of social reformers Samuel Gridley and Julia Ward Howe we can look at the small, not often discussed, queer community within the wealthy white neighborhood of 1800s Beacon Hill. In the 1800s, queer relationships looked and were defined very differently than they are today. The ambiguous intimate relationships between people of the same sex back then are often described as “Romantic Friendships.” These relationships often blurred the lines between romantic and platonic love. Based on what records are available, Senator Charles Sumner appears to have been in a “Romantic Friendship” with Samuel Gridley Howe. While we may never know how he identified, we know that he viewed his relationships with Howe as one of most significant relationships in his life.

Directions to next stop

Continue walking down Chestnut Street. Upon arriving at Charles Street, turn right and walk one block. At the intersection of Mount Vernon Street, cross the street. The former site of the Charles Street Meeting House is on the corner.

Charles Street Meeting House

Charles St. Meeting House has served as both a religious and community space.

Charles St. Meeting House has served as both a religious and community space.

Transcript

We are now at the Charles Street Meetinghouse, which has played a significant role in several communities since it was built in 1807. Originally housing the Third Baptist Church, the building became home to the First African Methodist Episcopal congregation in 1876 where it served as a religious center and gathering place for local activists. When this church left Beacon Hill in 1939, the building soon housed an Orthodox Alabanian Congregation. In 1968, it became home to a Unitarian Universalist Congregation under the leadership of Reverend Randy Gibson, and soon transformed into a safe space for the Boston LGBTQ+ community. Not only did the Meetinghouse provide a place to worship, it also served as a place of community gathering. It hosted social events such as movie nights and fundraisers for other queer community groups. It was also home to the first federally funded LGBTQ+ youth group, which started in 1974. Most notably, the Meeting House was the first home of Gay Community News, the first newspaper in New England exclusively for the gay community. This publication informed its readers about events and politics that concerned the LGBTQ+ community...things they could not find in mainstream publications. Starting as a four-page newsletter, Gay Community New quickly grew to a 16-page biweekly newspaper. In its inaugural volume, the editors stated the purpose of the paper: "There has been a long-standing need in the Boston gay community for improved communication between the various gay organizations and the gay individual... The Gay Community Newsletter is meant as a means to solve this problem..." Charles Street Meetinghouse provided early financial support as well as the physical space for the staff to meet and work in the early years of the paper’s publication. By 1974, the paper moved to another location downtown. Gay Community News published from 1973 until 1999 when it closed for a variety of reasons including financial difficulties and the rise of the internet. Throughout its twenty seven-year run, the paper provided news and resources, solidarity and information during the AIDS crisis of the 1980s, and served as a site of discussion and debate for the gay and lesbian community. Notable figures such as Elaine Noble, the first out lesbian elected state lawmaker, regularly used the newspaper to connect with the gay and lesbian community. The paper also offered a way for those whose voices were not heard or often ignored, such as Black gays and lesbians, to have a platform to speak. One group that used this forum were members of the Combahee River Collective, a Black lesbian association, who spoke out about how they were made to feel unwelcome and excluded at community events and rallies. The growing visible footprint of the LGBTQ+ community in Boston would not have been possible without the work of the activists nurtured at the Charles Street Meetinghouse and the welcoming supportive community they found there. An article published in Gay Community News reflects upon this legacy: "...the fact remains that CSMH is not a Gay Community Center, and in fact, not even a gay church. Our usage of the church is part of an historical progression, with another group filling our place as soon as we depart and further fulfilling the Meetinghouse’s historical role.”

In 1968, the Charles Street Meetinghouse became home to a Unitarian Universalist Congregation under the leadership of Reverend Randy Gibson, and soon transformed into a safe space for the Boston LGBTQ community. Not only did the Meetinghouse provide a place to worship, it also served as a place of community gathering. It hosted social events such as movie nights and fundraisers for other queer community groups. It was also home to the first federally funded LGBTQ youth group, which started in 1974. Notably, the Meeting House was the first home of Gay Community News, the first newspaper in New England exclusively for the gay community. This publication informed its readers about events and politics that concerned the LGBTQ+ community which they could not find in mainstream publications. Throughout its twenty seven-year run, the paper provided news and resources, solidarity and information during the AIDS crisis of the 1980s, and served as a site of discussion and debate for the gay and lesbian community.

Directions to next stop

At the intersection of Charles Street and Mount Vernon Street, cross Charles Street. Turn left up Charles Street. Walk two blocks and cross Revere Street. After crossing the street, look down and across Charles Street at the approximate location of the Sarah Orne Jewett and Annie Fields House.

Site of Sarah Orne Jewett and Annie Fields House

Former site of Sarah Orne Jewett and Annie Fields house

Former site of Sarah Orne Jewett and Annie Fields house

Transcript

Though no longer standing, 148 Charles Street is the site of the home of Annie Fields and Sarah Orne Jewett, two women who were in a Boston Marriage. A Boston Marriage typically refers to two, usually white, wealthy, college educated women who lived together in a monogamous and intimate partnership. Like the Romantic Friendships we discussed earlier, Boston Marriages blurred the line between platonic and romantic love and were known for their deep emotional connections. Though we do not know how Annie Fields and Sarah Orne Jewett self-identified, we can still look for clues to understanding their relationship through the ways they presented themselves...as a married couple in their social circle, sharing a house, and taking vows to each other. Annie Fields and Sarah Orne Jewett were integral to the thriving literary community in Boston, centered in their home. Fields, in particular, helped establish this community. Born into a wealthy family, and privately educated, she married James T. Fields at age 20. James was a publisher at the Old Corner Bookstore. A writer herself, Annie often acted as an editorial assistant for James, recommending and advocating for writers she liked. Skilled as a hostess, Annie often held literary salons here on Charles Street. Guests included artists and authors such as Charles Dickins, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Ralph Waldo Emerson, as well as the actress Charlotte Cushman. Cushman pushed 1800s gender boundaries by playing male roles in plays, by dressing in male clothing, both on and off stage, and by having several long-term romantic relationships with women. She later moved to Italy where she formed artistic collective with a number of women who were, like her, in same-sex relationships. Her friendship with the Fields shows a degree of familiarity and acceptance for queer lifestyles among Boston’s cultural elite, which is further illustrated with Annie’s later relationship with Sarah Orne Jewett. When James died in 1881, Annie entered into a Boston Marriage with Sarah. They split their time between Annie’s house in Boston and Sarah’s in Maine. Together, Sarah and Annie continued to cultivate a circle of literary and artistic friends. Within that circle, they were able to live openly and authentically as a couple. However, to the broader public, Jewett and Fields masked their marriage. For example, when Fields edited a compilation of Jewett’s letters for publication, she deliberately omitted explicit references to their relationship. Their genuine, authentic love for one another, however, is clearly shown in an unpublished poem written by Jewett to Fields: Do you remember, darling A year ago today When we gave ourselves to each other Before you went away At the end of that pleasant summer weather Which we had spent by the sea together? How little we knew, my darling All that the year would bring! Did I think of the wretched mornings When I should kiss my ring And long with all my heart to see The girl who gave the ring to me? We have not been sorry darling We have loved each other so- We will not take back the promises We made a year ago- And so again, my darling, I give myself to you, With graver thought than a year ago With love that is deep and true.

Though no longer standing, 148 Charles Street is the site of the home of Annie Fields and Sarah Orne Jewett, two women who were in a Boston Marriage. A Boston Marriage typically refers to two, usually white, wealthy, college educated women who lived together in a monogamous and intimate partnership. Boston Marriages blurred the line between platonic and romantic love and were known for their deep emotional connections. Though we do not know how Annie Fields and Sarah Orne Jewett self-identified, we can still look for clues to understanding their relationship through the ways they presented themselves...as a married couple in their social circle, sharing a house, and taking vows to each other. Annie Fields and Sarah Orne Jewett were integral to the thriving literary community in Boston, centered in their home. In their social circle, they were able to live openly and authentically as a couple.

Directions to next stop

With your back to Charles Street, walk up Revere Street. Turn left to walk up West Cedar Street. Turn right onto Phillips Street, making sure you are on the left side of the street. Prescott Townsend's Home is at 75 Phillips Street.

Site of Prescott Townsend Home

75 Philips Street home of Prescott Townsend

75 Philips Street home of Prescott Townsend

Transcript

You are now standing in front of the home of notable Gay Rights activist Prescott Townsend. Townsend grew up in the early 1900s in Roxbury and from a young age, was out to his family. They accepted him but warned Townsend to be careful, given that homosexual behavior was criminalized under the General Laws of Massachusetts. As a young man, Townsend joined the Naval Reserve and served in World War I. Following his service, he returned to Boston and attended Harvard Law School. After a year of law school, he decided to travel, and made his way to Paris and the artistic and cultural community there. Townsend wanted to bring the sense of artistic community he found in Paris back to Beacon Hill. He purchased a handful of shops and homes, which he rented out to local artists. He also opened the Barn Theatre, which served as the artistic center of Townsend’s Beacon Hill. This community blossomed until the Great Depression when Townsend lost all but two of his properties. He retained his home here on Phillips Street, and one behind it on Lindall Place. On January 29, 1943, authorities arrested Townsend for breaking the same laws his family had warned him about as a youth. He served an eighteen-month sentence at the Massachusetts House of Corrections on Deer Island. With this sentence, Townsend became an outcast. No family members came to his defense nor petitioned for his release. While he lost his family and the community that he had grown up in, it freed him to live even more openly in public, to express himself as he wanted, and devote himself to activism. In the 1950s, Townsend held meetings in his home every Sunday. He called these meetings "the first social discussion of homosexuality in Boston." By 1957, these meetings had become the first Boston chapter of the Mattachine Society, an early national gay rights organization. As an early gay rights activist, Townsend believed members of his community should be able to live their lives out in the open. At the time, this was a radical view, even for some members of the Mattachine Society. While Townsend had been publicly outed due to his arrest, many others preferred to stay quiet about their identities. They feared the loss of their livelihoods, whereas Townsend’s financial security allowed him to be more outspoken. Eventually Townsend split from the Mattachine Society so he could more freely continue his advocacy for gay Bostonians. He formed his own group, the Boston Demophile Society. They met up to his death in 1973. Unfortunately, little more is known about the organization or Prescott himself due to a housefire here in 1971, which destroyed most of his papers. As an eccentric patron of the arts and a vocal uncompromising activist, Townsend helped foster a community of artists and activists alike both here in Boston as well as in Provincetown on Cape Cod.

This is the home of Prescott Townsend, a pioneering gay rights activist in the 1900s. Coming from a wealthy family, Townsend helped cultivate an artistic community on Beacon Hill. After being outcast from his family following his arrest in 1943, Townsend lived even more openly in public, expressed himself as he wanted, and devoted himself to activism. In the 1950s, he held meetings in his home which became the first Boston chapter of the Mattachine Society, an early national gay rights organization. He later formed his own group, the Boston Demophile Society which met here until his death in 1973. As an eccentric patron of the arts and a vocal uncompromising activist, Townsend helped foster a community of artists and activists alike both here in Boston as well as in Provincetown on Cape Cod.

Directions to next stop

Continue walking along Phillips Street. Turn left onto Anderson Street. Turn right onto Cambridge Street, crossing Anderson Street. Stop at the corner of the next intersection (Garden and Cambridge Streets) for the next stop.

Sporters

Sporters Bar on Cambridge Street

Sporters Bar on Cambridge Street

Transcript

You’re standing at the former location of Sporters, which operated here from 1939 to 1995. Sporters got its start as a neighborhood bar, serving the working-class community living on the north slope of Beacon Hill. As more and more queer people moved into the neighborhood, it “officially” became a gay bar in 1957. Gay bars like this offered some of the only public places where queer people could meet each other. Though the threat of police raids was ever-present, bars such as Sporters were important to the formation of a collective identity and were instrumental in shaping the LGBTQ+ community as we know it today. For example, author John Read discussed the central role of Sporters in his 1973 memoir, The Best Little Boy in the World: "If you go to Sporters a couple nights a week, you are bound to see many of your friends. If there is someone you want to meet, sooner or later a friend will introduce you, or you will find yourself standing next to him, both of you knowing that it is time to say hello because you both have been smiling a little the past few times you’ve seen each other there." By the 1980s and 90s, the gay community in Beacon Hill had mostly disappeared, moving to trendier parts of the city. Sporters closed in 1995, a reflection of this decline and also part of a larger trend of queer venues shutting down. As the LGBTQ+ community has become more accepted by the wider society, and as they have fought and won various legal protections, many of these venues saw increasingly less patronage and closed their doors.

Sporters operated here from 1939 to 1995 and got its start as a neighborhood bar, serving the working-class community of Beacon Hill. As more and more queer people moved into the neighborhood, it “officially” became a gay bar in 1957. Gay bars like this offered some of the only public places where queer people could meet each other. Though the threat of police raids was ever-present, bars such as Sporters were important to the formation of a collective identity and were instrumental in shaping the LGBTQ+ community as we know it today. By the 1980s and 90s, the gay community in Beacon Hill had mostly disappeared, moving to trendier parts of the city. Sporters closed in 1995, a reflection of this decline and also part of a larger trend of queer venues shutting down.

Directions to next stop

Old West Church is located on the other side of Cambridge Street. Cross the street at this intersection (Garden and Cambridge Streets) and continue walking along Cambridge Street until you reach Old West Church (after Lynde Street).

Old West Church

Old West Church

Old West Church

Transcript

Similar to the Charles Street Meetinghouse, the Old West Church, established in 1737, has a long history as a welcoming space and gathering place for change. In the 1850s Minister Charles Lowell used the pulpit to advocate for social justice, the abolition of slavery, and the end of racial segregation. The congregation disbanded shortly after his retirement in 1887. After serving as a public library for a time, the building once again became a church in 1961. In the early 1970s, the building became home to the Metropolitan Community Church, or MCC, a queer branch of Protestantism. By 1974 MCC had choir, weekly services, Sunday school, prayer groups, bible studies, and more, as one of the only queer Christian organizations in the city. A uniquely Christian and queer community space, MCC welcomed the Gay Liberation movement. Playing a similar role to the Charles Street Meetinghouse, the Old West Church hosted numerous events, authors, speakers, and benefits associated with gay rights and culture. By the mid-1970s, Old West Church became a major gathering place for LGBTQ+ activists to convene as they tackled a whole new set of challenges they would face in the coming decades. For example, in 1978, a call went out to find a safe place to discuss the police raids on homosexuals at the Boston Public Library. The Old West Church responded by offering its halls to a group that would eventually become the Gay and Lesbian Advocates and Defenders, also known as GLAD. One of the original members, Richard Burns, remembered: "So when GLAD was formed, there were five of us in a church basement, Old West Church on Beacon Hill. John Ward was the leader, Cindy Rizzo, me, Roberta Stone – we incorporated, and I became the President of the board, John became the volunteer executive director. And, today it’s this wonderful, wonderful, equality machine that I’m so proud still exists." John Ward became a prominent lawyer in Boston representing gay members of the community fighting for the right to exist publicly and without harassment. In one of his first major cases, Doe v. McNiff, Ward successfully represented a “John Doe” who sued the Boston Public Library and police officials for depriving him of his civil rights, stemming from the Boston police raids. GLAD later advocated for “6 by ‘12,” the campaign to achieve marriage equality in all 6 New England states by 2012, missing their goal by only one year when Rhode Island finally legalized same sex marriage. Today the Old West Church remains a community space for the Queer Christian community. Still home to MCC, members carry on its tradition of social justice and activism. Leaders and members participate in Pride Marches and continue to advocate for a better future for all.

In the early 1970s, Old West Church became home to the Metropolitan Community Church, or MCC, a queer branch of Protestantism. By 1974 MCC had choir, weekly services, Sunday school, prayer groups, bible studies, and more, as one of the only queer Christian organizations in the city. A uniquely Christian and queer community space, MCC welcomed the Gay Liberation movement. Old West Church hosted numerous events, authors, speakers, and benefits associated with gay rights and culture. By the mid-1970s, Old West Church became a major gathering place for LGBTQ+ activists to convene as they tackled a whole new set of challenges they would face in the coming decades. For example, in 1978, a call went out to find a safe place to discuss the police raids on homosexuals at the Boston Public Library. The Old West Church responded by offering its halls to a group that would eventually become the Gay and Lesbian Advocates and Defenders, also known as GLAD.

Directions to next stop

Cross back over Cambridge Steet to and stand on the corner of Cambridge and Temple Streets. Look up Temple Street as you listen to the next stop.

Angelina Weld Grimke Early Childhood Home

Temple Street, site of Angelina Weld Grimke's childhood home

Temple Street, site of Angelina Weld Grimke's childhood home

Transcript

Born into a biracial family in 1880, the poet and playwright Angelina Weld Grimke lived her earliest years here on Temple Street, in a neighborhood long known as a hotbed of Black activism. She came from a family of prominent activists and thinkers. Her father Archibald had escaped slavery and became a lawyer and leading civil rights activist in Boston and beyond. Her great aunts, Angelina and Sarah Grimke, were Quaker activists in both the abolition and suffragist movements as well. In keeping with the legacy of her activist family, Grimke thought and wrote deeply and extensively on the pressing issues of race and discrimination. Her 1916 play Rachel focused on a Black family coping with the lynching of their father and brother. Her short stories, poems, and other writings were published in magazines and journals including Opportunity and The Crisis, two major Black publications, as well as several anthologies of poetry from the Harlem Renaissance era. It is in her unpublished papers and poems, however, where Grimke found the freedom to express her love for other women. Though society at large, and her father, in particular, looked firmly down upon her attraction to other women, Grimke found her voice in her private writings. For example, in one letter to her friend Mary Burrill, who later became a playwright as well, a 16 year old Grimke wrote: "My own darling Mamie, I hope my darling you will not be offended if your ardent lover calls you such familiar names. ... Oh Mamie if you only knew how my heart beats when I think of you and it yearns and pants to gaze, if only for one second, upon your lovely face. ... I know you are too young now to become my wife, but I hope darling, that in a few years you will come to me and be my love, my wife!" It is unclear if Grimke ever engaged in a long term relationship with another woman. Publicly swearing off romantic relationships, she spent most of her time teaching, writing, and caring for her sick and aging father. However, her longing for and denial of love is a persistent theme in her work. Unable to live as her authentic self, she expressed her desires through her poetry, some of which remained unpublished until after her death...including her poem “Rosabel”: Leaves, that whisper, whisper ever, Listen, listen, pray; Birds, that twitter, twitter softly, Do not say me nay; Winds, that breathe about, upon her, (Since I do not dare) Whisper, twitter, breathe unto her That I find her fair. Rose whose soul unfolds white petaled Touch her soul rose-white; Rose whose thoughts unfold gold petaled Blossom in her sight; Rose whose heart unfolds red petaled Quick her slow heart's stir; Tell her white, gold, red my love is; And for her, — for her

Born into a biracial family in 1880, the poet and playwright Angelina Weld Grimke lived her earliest years here on Temple Street, in a neighborhood long known as a hotbed of Black activism. She came from a family of prominent activists and thinkers. In keeping with the legacy of her activist family, Grimke thought and wrote deeply and extensively on the pressing issues of race and discrimination. It is in her unpublished papers and poems, however, where Grimke found the freedom to express her love for other women. Though society at large, and her father, in particular, looked firmly down upon her attraction to other women, Grimke found her voice in her private writings. It is unclear if Grimke ever engaged in a long term relationship with another woman. Publicly swearing off romantic relationships, she spent most of her time teaching, writing, and caring for her sick and aging father. However, her longing for and denial of love is a persistent theme in her work.

Directions to next stop

Continue walking along Cambridge Street as it curves. Stop at the cross-walk across the street from the Government Center MBTA entrance to learn about Scollay Square.

Scollay Square

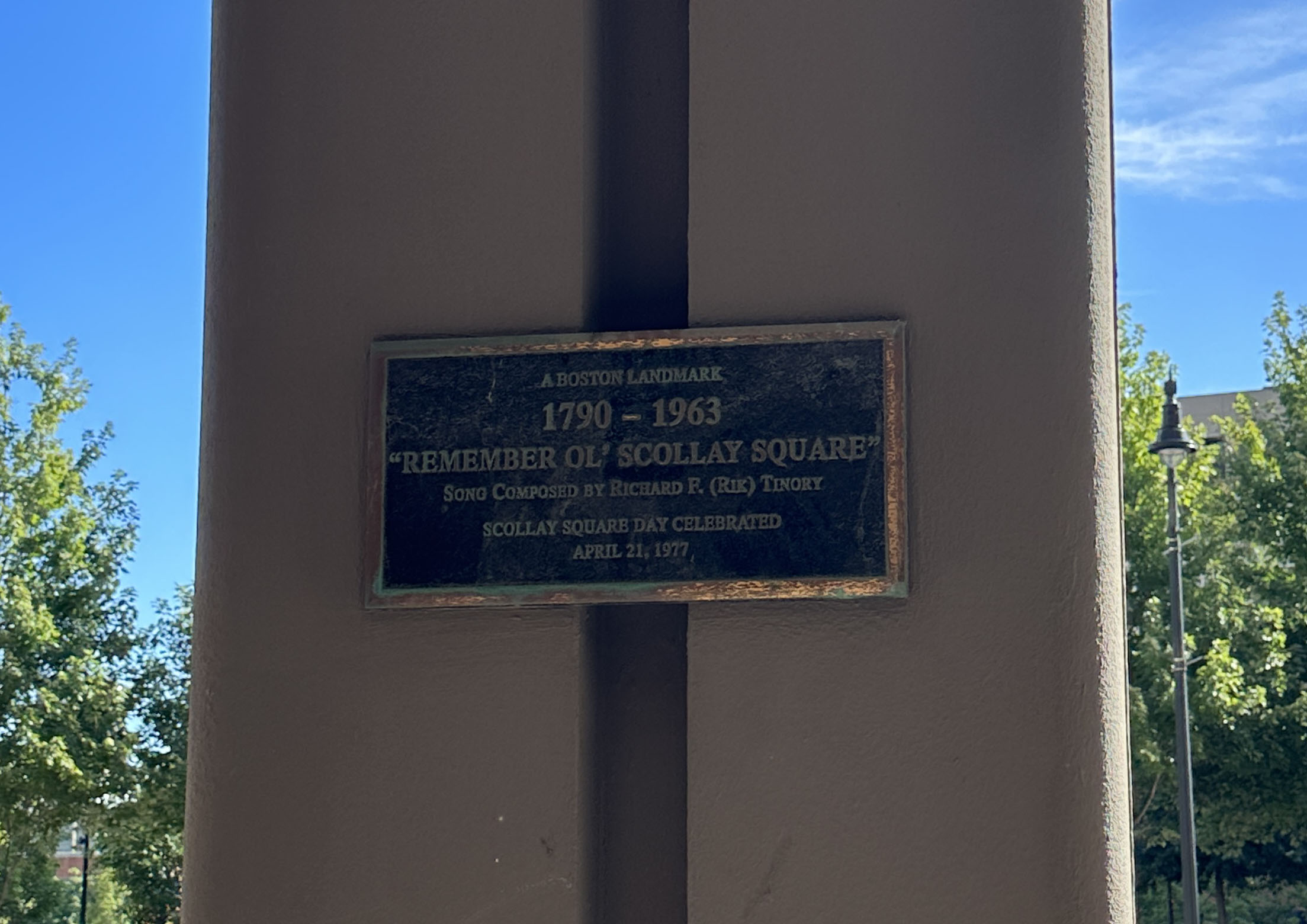

Scollay Square plaque on Cambridge Street

Scollay Square plaque on Cambridge Street

Transcript

As we stand here today in Government Center, the only tangible reminders that this area was once a bustling commercial and entertainment hub is a plaque on a pillar of One Center Plaza that implores us to “Remember Ol’ Scolly Square,” and a sign in the Government Center T station that tells us it was once “Scollay Under.” Before urban renewal efforts in the 1960s, this area was a much different place. Scollay Square hosted a number of bars, restaurants, tattoo shops, hotels and theaters that attracted a wide variety of clientele including local Bostonians, sailors on leave from the Charlestown Navy Yard, and members of the queer community. As an adult entertainment district, Scollay Square was an integral part of Boston’s night life. Theaters such as the Howard Athenaeum and others hosted burlesque shows some of which featured female and male impersonators, later known as drag queens and kings. One of the most famous drag queens in the city was Sylvia Sidney, who pushed gender boundaries in his performances but always used he/him pronouns. Known for his vulgarity and a self-described “hard-core madam,” Sylvia’s career spanned from 1947 to almost the time of his death in 1998. In addition to hosting a wide variety of queer performers, Scollay Square was a haven for queer patrons, who found opportunities to explore their own identities and community in the neighborhood’s bars and nightlife. During the urban renewal projects of the 1950s and 60s, however, city planners and leaders set their sights on Scollay Square and other such downtown areas and businesses for demolition. They tried to gain support for these projects by reminding Bostonians that these were seedy, unsavory neighborhoods and a blight on the reputation of the city...places for criminals and deviants. Though not specifically referencing Scollay Square, city councilor Fred Langone was explicit in his motivations for targeting gay bars for demolition in a 1965 meeting: "We will be better off without these incubators of homosexuality and indecency and Bohemian way of life. I tell you right now, we will be better off without it and if we accomplish nothing else, at least we will uproot this cancer in one area of the city." Ultimately, the City got its way. Scollay Square, where many people, including those in Boston’s queer community, found refuge, joy, entertainment, and each other, was demolished to make room for the government buildings that you see here today.

Though no longer standing, Scollay Square hosted a number of bars, restaurants, tattoo shops, hotels and theaters that attracted a wide variety of clientele including local Bostonians, sailors on leave from the Charlestown Navy Yard, and members of the queer community. As an adult entertainment district, Scollay Square was an integral part of Boston’s night life. Theaters such as the Howard Athenaeum and others hosted burlesque shows some of which featured female and male impersonators, later known as drag queens and kings. In addition to hosting a wide variety of queer performers, Scollay Square was a haven for queer patrons, who found opportunities to explore their own identities and community in the neighborhood’s bars and nightlife. During the urban renewal projects of the 1950s and 60s, the City demolished Scollay Square to make room for the government buildings that you see here today.

Directions to next stop

Cross the intersection towards the entrance of the Government Center MBTA entrance. Walk to the right around the station, going down the curved pedestrian street. At the Bill Russell statue, turn left and stand at the top of the staircase in front of City Hall and facing Faneuil Hall.

Boston City Hall

Faneuil Hall from City Hall Plaza

Faneuil Hall from City Hall Plaza

Transcript

We are now standing between City Hall and Faneuil Hall, the last stop of our tour. Both of these sites are strongly tied to the LGTBQ+ history of Boston. Down the steps and across the street sits Faneuil Hall, a crucial gathering place for Bostonians since it first opened its doors in 1742. The Hall was the home of town meeting and the site of some of the earliest protests of the American Revolution. It continues to serve as a gathering space for discussion, debate, and protest. Beginning in the 1970s, gay and lesbian Bostonians began using the hall for similar purposes. According to Town Hall Organizers in 1989: "Town Meeting has been a New England tradition for centuries, exemplifying the spirit of grassroots citizens’ democracy which is this region’s heritage. New Englanders have long gathered to address the issues facing them, both large and small, in an open, participatory, and lively forum. The model is one of the citizenry taking direct responsibility for their own lives and affairs. Fusing New England tradition with the more modern rite of Lesbian and Gay Pride, the lesbian and gay community of Greater Boston has held its own town meetings in historic Fanueil [sic.] Hall for years... " Gay and Lesbian Town Meetings gave space for the community to discuss and raise awareness for pressing issues including equal rights and justice, as well as the AIDS crisis of the 1980s. For example, at the 1987 Town Meeting, activist Larry Kramer gave a speech titled “I Can’t Believe You Want To Die” urging the LGBTQ+ community to force political leaders to take the issue seriously. Another town meeting ended with a candlelight vigil walking from Faneuil Hall over here to City Hall to draw attention to the local government’s failure to address the crisis. But City Hall is not just a site of protests and vigils...it is also a place of triumph and joy. On May 17, 2004, three of the couples who were plaintiffs in the Goodridge v. Department of Public Health case, which solidified marriage equality in Massachusetts, lined up at City Hall to get their marriage licenses. The Boston Globe wrote of the event: "The first three marriage licenses the City of Boston issues this morning are reserved for three of the seven plaintiff couples whose courageous appeal to the state’s highest court brought Massachusetts to this historic day...This is as it should be. The question of gay marriage has always been, simply and fundamentally, about people – their dreams, their rights, and their love...It is also a day for Massachusetts citizens to take pride in once again being at the forefront of revolution... " ... Boston historic LGBTQ+ community played an integral role in the continuing American conversation. As we come to the end of our tour, consider the ways this community asked and answered the fundamental American questions - about freedom, voice, and how change is made - in their own time and ways. What can we learn from them as we ask and attempt to answer those same questions today? The staff at National Parks of Boston extends thanks to our friends at the History Project for their thoughtful and meaningful contributions to this tour.

Beginning in the 1970s, gay and lesbian Bostonians began using Faneuil Hall to host Gay and Lesbian Town Meetings. These meetings gave space for the community to discuss and raise awareness for pressing issues such as equal rights and the AIDS crisis of the 1980s. On May 17, 2004, three of the couples who were plaintiffs in the Goodridge v. Department of Public Health case, which solidified marriage equality in Massachusetts, lined up at City Hall to get their marriage licenses. The Boston Globe wrote, "The first three marriage licenses the City of Boston issues this morning are reserved for three of the seven plaintiff couples whose courageous appeal to the state’s highest court brought Massachusetts to this historic day...This is as it should be. The question of gay marriage has always been, simply and fundamentally, about people – their dreams, their rights, and their love...It is also a day for Massachusetts citizens to take pride in once again being at the forefront of revolution."